The Healing Influence of Eurythmy in Schools

One of the first questions parents ask when they come to learn about a Waldorf school for their child is about the movement art taught in most Waldorf schools: eurythmy. What is it? Why does my child have to do this? After many years of working as a eurythmy teacher and in Waldorf schools’ administration I find myself still answering these questions. Yet the answers grow and develop as the years pass and new knowledge both in science and education bring light to bear on the questions.

Between and Beyond

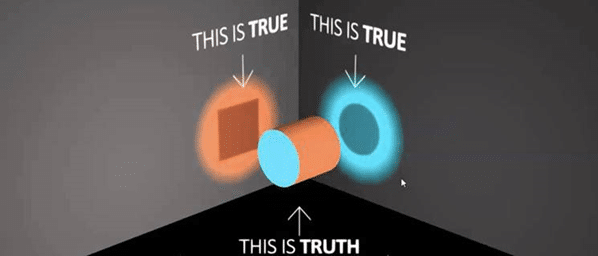

In a binary way of seeing, the world is comprehended in pairs of “either/or”. William Blake, in a letter to his friend Thomas Butt, identified this way of seeing as the approach of reductionist science, or what he famously called “Single vision & Newton’s sleep”. On this view, movement — both inner and outer — is accounted for in the logic of cause and effect, and indeed, purely physical events, like a rock falling to earth, can be adequately described by the laws of causality or “if/then”. (Even Albert Einstein, with his theory of relativity, would agree that the earth is more the cause of attracting a falling rock than the rock would be the cause of attracting a rising earth.)

Developing the Art of Imagination through Creative Speech

Creative Speech formation makes us better teachers: clearer in our instructions, increasingly enlivened in our storytelling, more soulful in our poetry, and more objective in our experiences. We can listen with greater depth and grasp what — and why — our students don’t understand. We can experience their spirit and soul in words because we have done it for ourselves. When working out of Creative Speech formation in our teaching, our ego sense fully engaged.

When It’s Safe to Move

As of this decade, every child enrolled in an American educational institution — from early childhood programs through high school — entered life on earth sometime after the U.S. was shaken by an attack of four hijacked commercial jets during the clear mid-morning of 11 September 2001. We have yet to weigh the full measure of consequence wrought on young souls by this assault, the only major foreign attack on civilian home targets this country has experienced in close on two centuries. Yet we can already say this much: children born in this country since that date, though they may have come “trailing clouds of glory”, are growing up in a culture much more conscious of security, much more concerned about germs and allergies, and much more restrictive in what teachers — parents, too — are allowed to risk with the youngsters in their care.

An Ode to Eurythmy: Reflections on Why We Need Eurythmy in Our schools and in Teacher Education Programs

My first experiences with eurythmy occurred when I was four years old. A small group of children in Spring Valley, NY was given the opportunity to enjoy some stories, verses, and songs in movement with Lisa Monges. She taught us in her large living room (the space that is now the Fellowship Community for the elderly) and I remember the unusual experience of being in a larger group, wearing red overalls and funny slippers, and meeting new children through movement. As a dreamy Waldorf student in the years that followed, I had eurythmy twice a week throughout the grades and into high school, even doing some additional individualized therapeutic work to help with back problems one year. I remember in particular the experience in 7th grade when we were asked to write poems and then the eurythmy teacher did them with us in class. Much to my surprise, my poem was better in movement!

Practicing Tri-Une Thinking

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was the poet and scientist who perhaps offered the closest thing to a protocol for cultivating what in an earlier essay I have called mobile tri-une thinking. To be sure, he was not a systematic writer, and the four steps that follow are not to be found anywhere in his rambling body of work.