Our focus for this issue of Center & Periphery shifts to the East: first to Forest Row, where Georg Locher — beloved mentor, teacher, artist, and genial uncle to the programs sponsored by the Center for Anthroposophy — passed away on 15 December 2014, just a few months after celebrating his 80th birthday.

Our focus for this issue of Center & Periphery shifts to the East: first to Forest Row, where Georg Locher — beloved mentor, teacher, artist, and genial uncle to the programs sponsored by the Center for Anthroposophy — passed away on 15 December 2014, just a few months after celebrating his 80th birthday.

Then our gaze shifts yet further towards the Orient to embrace an international gathering in the Levant or Holy Land of leading Waldorf teachers from around the world — the first of its kind in nearly a century of Waldorf education.

Returning to the West and turning our attention to the future, we also offer you brief previews of this coming summer. We invite you to join us on this pilgrimage to the East and back again.

— Douglas Gerwin, Director

Center for Anthroposophy

In this Issue

Dateline Forest Row, England: Portrait of Georg Locher

Eulogy composed and delivered by Adrian Locher at the funeral of his father in Forest Row, England, on 19 December 2014, with afterword by Torin Finser

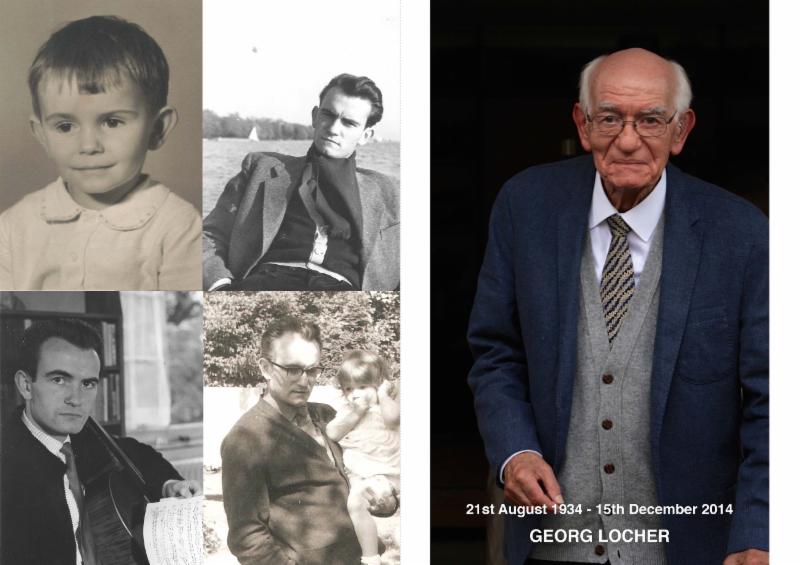

Georg Locher

21 August 1934 – 15 December 2014

Georg Johannes Locher was born on 21st August 1934 in Zurich, Switzerland.

His parents, Hans and Tilde Locher, were both early anthroposophists who had encountered Rudolf Steiner and attended his lectures. Hans put Steiner’s ideas on the threefold social organism into practice in his family business, Leder-Locher (making and selling leather goods), which still exists today as a chain of shops in several Swiss cities and still gives 25% of its profits to cultural life. Tilde, whose maiden name was Grosse (sister of Rudolf Grosse), worked with her husband as a secretary in the business. She also took short-hand reports of Steiner’s Zurich lectures.

Georg was the third of three children. He is survived by his brother Thomas, a geologist, and his sister Angela, a eurythmist.

Georg was born in the sign of Leo. His favorite animal was the lion, which in his youth he used frequently to observe and sketch at Zurich Zoo, and of which there were always numerous pictures in his homes. (Even his password for his computer was ‘lioncub’!) Interestingly, Leo is connected to the heart, and Georg was born with a heart condition, a ‘hole’ in the heart. This gave his childhood a certain color. He needed a lot of extra care and protection by those around him, notably his parents and siblings. He was often sickly and needed special food. He was extremely sensitive and had a great love of animals, especially his little dachshund, from which he was inseparable.

At the age of seven, when he was ready to start school at the Zurich Waldorf School, he refused to go. He had a real resistance to school, and even when his teacher kindly offered to coach him at home he didn’t want it (an interesting fact for a future teacher). This went on for almost a year. Then, one day, he was taken to a Mozart concert. The next day he announced he wanted to go to school. Georg used to describe this as the ‘Mozart effect’!

In his teens Georg was part of the ‘Wander Vogel’ youth movement and, despite his heart condition, often went walking or skiing in the Swiss Alps (though on one occasion he had to make a sudden departure from a climb due to failing breath).

The picture of his childhood and youth is one of a certain fragility and need of protection. However, his heart condition did excuse him from doing his required Swiss army service.

It is interesting to note that this weakness of the heart did not persist during his life, since his heart appeared to get stronger. In the end, he did not die of heart failure, but of a cancerous condition in the liver; indeed during his last weeks, when his other organs were shutting down, it was his heart and lungs that persisted the longest. One could say that through his life he made a strength out of an initial weakness, his spiritual Lion heart overcoming the physical weakness through the development of extra strong heart forces.

As the Zurich Waldorf School at that time did not extend past the eighth grade, and through the encouragement of a particular much loved English teacher, it was decided that Georg would enroll for his eleventh grade at Michael Hall School in England.

A story Georg liked to tell was that in his early teens he had seen a photo of a girl on horseback in a nature magazine, with the caption: ‘Girl somewhere in England’. This had for some reason impressed him and stuck in his mind. One can only imagine that, when he arrived at Michael Hall’s boarding hostel in Kidbrooke Mansion, then run by Francis and Elisabeth Edmunds, and first set eyes on their twelve year-old daughter, Angela, he must have thought: ‘Here is the girl somewhere in England!’ She was, in fact, his future wife and possessed that quality of freedom and natural beauty which he had been drawn to in that photo of the girl on horseback.

It was, indeed, a momentous event for Georg, a life-determining moment of destiny. Not only had he met his future wife, but also his future teacher of Waldorf education, Francis Edmunds, and the school at which he himself would come to teach for so many years. And all this at the tender age of 16!

However, before he could pick up this life that seemed to have been laid out before him, there was a period of separation. And although Georg and Angela had certainly noticed each other during his time at Michael Hall, with some sweet exchanges of an artistic nature (e.g. a portrait of Angela drawn by Georg for the Edmunds), when he left at the end of the eleventh grade, it was to be seven years before they would meet again.

After returning to Zurich, Georg entered a period of life dilemmas. What vocation should he pursue? Was he to follow in his father’s footsteps by entering the family business? To his father’s disappointment, the answer was ‘no’. Should he pursue an academic career and go to university? After twice failing the college entrance exams, the answer was also, clearly, ‘no’. After three years of trials, then, he decided to pursue the artist’s way, which clearly suited him best, and which he had already been pursuing throughout his youth. But the dilemmas continued. Was it to be painting, sculpture, drama, or music? It could have been any of these. Eventually he settled on music and went to study the cello at the Winterthur Conservatoire. For a few years afterwards he lived as a professional touring cellist, playing in orchestras throughout Germany and Switzerland. Photos of him at this time show a deeply sensitive, brooding young man, a real Romantic, living the dream.

Being a professional cellist, however, was not to be his ultimate vocation. During this time in Zurich an interest in anthroposophy had been growing in Georg, as he had been asked to play the cello for numerous anthroposophical festivals and events. Then, on a concert tour of England at the age of 24 with his school friend Peter Ramm, Georg stopped by at Michael Hall to visit the Edmunds for Christmas. There he met Angela again. By then she was 20 and enrolled in a teacher training program at Bognor Regis College. The spark between them was rekindled and two years later they were married. This, together with his growing wish to serve anthroposophy in a practical way, contributed to his decision to join the Waldorf teacher training which Francis Edmunds was running at Michael Hall. And from then onwards he never looked back. He had found his life’s vocation: Waldorf education. Here he could realise the multi-artist that he was, through painting, clay-modelling, drama, and of course, always music. But he added another art to the list: the art of education, which would bring him ever more deeply into the social realm.

He started teaching at Michael Hall at the age of 26 — initially German, Religion, and Art before taking a grade four up to grade eight. After this he completed two sets of grades one to eight. One can certainly say he did his bit of grade teaching! Year after year he prepared for main lessons, put on plays, organised and went on school trips, wrote reports, as well as being chairman of college several times. Throughout this time he was also always active as a cellist in school and local concerts and events.

During this time he and Angela were raising their five children: Eunice, Adrian, Rowena, Karin, and, a good deal later, Dominic. Their various homes in Forest Row were hubs of life, particularly the last, Priory Mead, which was right next door to Michael Hall and where he lived for 43 years until his death. In this respect, Georg was a true Englishman: his home was his castle and he, of course, was lord of castle! Priory Mead was especially such a castle for him. Here he created a beautiful music room/study that served not only as a place of retreat from his busy schedule (and bustling family) but also provided the scene for many a concert, gathering, or celebration. Throughout the years of family life, numerous boarders and friends filled out the Locher household, and many have remained in touch, fondly remembering their time in this special home.

Alongside his teaching at Michael Hall, two further strands began to develop in his life: the teacher training at Emerson College (part time at first) and annual trips visiting schools in North America. By 1986 he had resigned from Michael Hall and taken up a full-time post at Emerson College, co-running the education course with John Thompson. His trips to North America had increased from once to two or three times a year. He started to live on two continents. He later also became a schools advisor with the Steiner Schools Fellowship, making annual visits to many of the schools in Great Britain, notably Edinburgh, Wynstones, and South West London.

Georg’s connection to North America was strong and somehow symptomatic of a certain deep soul striving. As if England wasn’t sufficiently far “west” for this Swiss man, Georg’s orientation was to go further westwards, where he would find a greater soul freedom than he had found in England. It was noticeable to his friends and family that he would return from his American trips somehow changed — freer and happier. The friendships and colleagueships there seemed somehow easier, with stories of ‘going out to the movies’ or ‘going for ice cream’, things he rarely did in England. In addition to visiting schools, his annual visits included being an adjunct faculty member of the Waldorf teacher education programs at Antioch University New England and the Rudolf Steiner Centre Toronto. For many years he was on the board of the Rudolf Steiner Institute, an annual summer school for anthroposophy on the East Coast of the U.S. He was also the inspiring force behind the Renewal Courses for teachers at the Center for Anthroposophy in Wilton, New Hampshire, of which he was a founding board member (also its president) and where he gave courses for more than a decade.

Georg once said he never wanted to become ‘dead wood’ in an institution, and both with Michael Hall, and later Emerson, he was quick to move on before this could happen, trusting others to carry on the work. However, with his work in American it was a stroke in 2011 that prevented him from continuing. This was a great sadness for him during his last years, as he missed the life of friendships and colleagueships he had developed there. It was, therefore, a particular joy when, just a week before he died, his friend Torin Finser came especially to his bedside in hospital with a pile of letters and good wishes from his American friends, expressing gratitude for all he had done for them and how much he had meant to them. A torrent of emails followed, many from former students and teachers he had mentored over the years. Two words stand out particularly from these communications: ‘mentorship’ and ‘kindness’. The teachers he visited in their schools, many of whom he had formerly taught, felt deeply supported and accompanied by him. He both fully accepted them and encouraged them to develop further as teachers and human beings. He was famous for his ‘little chats’, in which he would take someone aside and point out a short-coming, suggesting a possible new direction, but always with utmost kindness.

In the years after his stroke, when he could no longer travel, Georg turned his attention to his family and home and to enriching the cultural life of the local Sussex Anthroposophical Society. Through his careful management and insistence on high standards the festivals in Forest Row became beautiful, artistic events which attracted larger numbers of people than usual. He was a master of detail, an artist-soul with a certain particularity much appreciated and enjoyed by those who knew and loved him.

Afterword added by Torin Finser:

With the support of my colleagues, I was able to fly to the UK and spend a day with Georg just a week before he crossed the threshold. The visit occurred on December 6th, itself a remarkable “coincidence” as Georg had frequently played the part of St .Nick during his lifetime. My brief visit with Georg on that day turned out to be a moving and transformative experience for me.

On the day before I arrived, Georg had fallen into a deep sleep, and the family had almost called off my visit. So when I walked into his hospital room, I was prepared for a one-way conversation, which is what happened for the first hour. My hands were filled with cards and greetings from friends all across the USA, some of which I read to the sleeping Georg. In between long periods of silence, I also prayed and sang for him (it seemed his breathing changed during my rendering of “Dona Nobis”). After an hour I got up to stretch my legs, feeling that I had done all I could to say goodbye.

I was standing at the end of a long hallway, looking out a window with many dead trees surrounding a single lone pine at the top of the hill, when a nurse came running toward me. “Are you Torin Finser? He is asking for you!”

When I entered Georg’s room for the second time, he was now fully awake and mostly his old self. His first words were: “Why are you here? I am not dying!” After some reassurances, he continued more philosophically, “How much time do we have left?”

What followed for the next hour was a most remarkable conversation, rich in memories of mutual friends, teacher training, USA visits, the arts, and even cigar smoking. A few details were mixed up, but for the most part there was a clear train of thought for conversation. He said he was not an artist but rather a teacher who tried to show an artistic way of education. Georg lit up and asked for his glasses when he was given Karine’s card with her painting “Angel Rising”. He then said that it was his dying wish that his childrenh visit Renewal, at which point, all five of them said emphatically, “We will!” Georg broke into a joyous smile. Thus it was especially satisfying for Georg that his children would finally connect with the other part of his life work. After much more conversation, including his role as founding president of the Center for Anthroposophy, he seemed tired and I told him we would withdraw for a while. He then said, “I need a little break to reflect on my dwindling thoughts.”

We retreated and the nurses came in to tend to Georg. Fifteen minutes later we returned but he was no longer with us in consciousness. He no longer recognized anyone, and started speaking incoherently, a kind of death march had set in. I felt that he had decided to embrace his approaching death, and was prepared to do it with characteristic determination. I waited another hour, we tried singing (to no avail) and then I rose to say goodbye. As I leaned over him and held his hands, I thought there was once again a flicker of recognition and he said, “Glorious death.” And as I turned to leave the room I heard him utter one more word: “Anthroposophy.”

Georg lingered in body for another week, though he never fully regained consciousness. Two weeks later, after the funeral service in the UK, some two dozen of his friends gathered in the Garden Room at the home of Alice and Trauger Groh in Wilton, NH on the 28th of December to share memories. The evening opened with cello music, included a reading of Adrian’s speech (see above), my recollections as retold here, and many, many contributions from the friends who had gathered. We also sang the same carol that was listed on the Forest Row funeral program, “Lo, How a Rose”. The beginning and end of the evening featured a well-known verse by Rudolf Steiner, in this case dedicated to our dear friend and colleague, Georg Locher.

May love of hearts reach out to love of souls,

May warmth of love ray out to Spirit-light.

Even so would we draw near to you,

Thinking with you Thoughts of Spirit,

Feeling in you the Love of Worlds,

Consciously at one with you

Willing in silent Being.

– Rudolf Steiner

Dateline Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Harduf: IF-WE Meet Again

Twice a year the International Forum (IF) for Waldorf/Steiner Education convenes to take the pulse of Waldorf schools around the world. Douglas Gerwin, who recently joined this group as a representative from North America, reports on the latest proceedings.

One of the joys of visiting Waldorf schools in any country is the opportunity to witness certain rituals that are shared throughout the world. One of them is the Morning Verse (“Morgenspruch”) that children stand to recite together with their teacher at the start of each school day.

Though my knowledge of Hebrew is limited to a single word (“Shalom”), I was easily able to follow this recitation during a recent visit to several Waldorf elementary and high schools in the run-up to a meeting in Israel of the International Forum for Steiner/Waldorf Education (“IF” for short, and originally named the “Hague Circle”). From the strong cadence of the verse and the lilting tone of the students’ voices, it was possible to discern each line of this familiar verse, even though the actual words were literally quite foreign to my ears.

Likewise paintings on the walls of the lower school expressed the well-known archetypal relationships of the primary colors, while the corridors of the high school were adorned with familiar yet original studies in black-and-white. But other aspects of the lessons I observed were distinctly indigenous. For instance, Hebrew is written from right to left — but not so, it turns out, when it comes to algebraic equations or geometric proofs, which teachers write from left to right. These sudden changes in direction require some nimble boardwork, especially if they form part of a narrative on the blackboard, since one needs to leave enough space in the sentence to add the equation without it colliding with the sentence. Musical scores, too, are read from left to right, even if the words are in Hebrew and therefore (from the Hebraic perspective) have to be read “backwards”.

Lower schools are enjoying steady and increasing enrollment, but the situation at the high school level is more problematic. In general, Jewish high schools tend to specialize–starting as early as the seventh grade–in the arts or sciences or crafts or performing arts, a direction opposite to the Waldorf ideal of providing a more all-rounded curriculum. At the upper end of the high school program, preparation for state exams cuts deeply into the daily schedule of the final two high school years. Not surprisingly, therefore, the schools struggle mightily to find–and train–high school teachers with Waldorf background.

Graduates of Jewish high schools face several years of national service before they can enter college. Men serve at least three years, women two, often in non-combat settings. Then most take a “gap year” before starting up a four-year college program, with the result that many do not complete their first degree until their late 20s. Exceptions to this rule are Moslems living in Israel, since they are not subject to conscription into the Israeli army.

At least in some classroom settings, English is the lingua franca. One of my hosts, a college professor of architecture, described how her Jewish university students speak no Arabic and her Moslem students speak no Hebrew. If she gets stuck in a lesson, she has to resort to English, a language that most residents in Israel learn, starting as early as the first grade. At least one Waldorf school in Israel is trying to remedy this cultural chasm by teaching Hebrew to Moslem students and Arabic to Israeli students.

Meeting of the International Forum (IF)

Those participants of the International Forum who arrived early in Israel had a chance to visit Waldorf schools in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv before driving north to the Harduf kibbutz, where the three-day IF meeting took place. Formerly known as the Hague Circle (in recognition of its original home base in the Netherlands), the IF is comprised of about 45 representatives from some 30 countries; roughly two-thirds come from Europe, with the remaining third from the other continents including the Americas (7), Australasia (5), Africa and the Middle East (3). Once a year it meets at the Goetheanum in Dornach and once in some other country where Waldorf education is practiced.

To leaven these meetings, we had several chances to see students in action, including a production of Nutcracker Suite that combined eurythmy with marching toy soldiers and dancing fairies accompanied by a small chamber ensemble. We were struck by the students’ enthusiasm for learning and their openness to foreigners. Wherever we went we were greeted by broad smiles and warm-hearted expressions of “Shalom!” It was also striking how intently these children looked into the eyes of their teachers when they are being addressed.

The Mission of Israel

Gilad Goldschmidt, genial host to the IF during our stay in Israel, presented a compelling picture of the mission of the Jews and of modern-day Israel. Drawing upon the writings of Rudolf Steiner, Gilad described how the task of the Ancient Jewish tribes was to bring intellectual thinking–“thinking as we know it today”–into the mainstream of human development. As he put it, “Abraham was the first person to think as we think.” Already 2,500 years ago Israelis–who call themselves “the people of the Book”–created the first culture in which all men and some women learned to read. In the Orthodox tradition, all boys begin to read and write from the age of three. In fact, the Hebrew word for “school” is “the House of the Book”.

As is well known, the Hebrew tradition (likewise Islam) outlaws any image of God. God is not to be pictured or carved, only conceived in abstract thought. (Islam applies this abstract form of thinking in the pursuit of science and technology.) Because they were denied the option of developing the pictorial, sculptural arts in their religious practice, the Jews developed a highly musical, poetic culture, with strong heart forces and a strong sense of caring for community or tribe. Indeed, Israelis are a nation of singers. Assemblies we attended spontaneously erupted into song, quite apart from the organized pieces that graced their festive events.

Waldorf education provides the opposite to this stream of abstract, image-less thinking. The mission of Waldorf education, then, is to lift objective consciousness into imaginative consciousness, a new form of living image-thinking, without however losing the “I” that has accompanied the development of abstract thinking. In this sense, Waldorf education serves as a countervailing “therapy” for the overly abstract “bookish” education that can be found in the Jewish/Islamic culture. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that Waldorf education is subject to attack from Orthodox quarters.

Future Dates

The next meeting of the IF will take place in Vienna (May). A year from now the Forum will make its first foray into the breadth of North America, starting in New York City, (November 14-15), then fanning out in small groups to visit Waldorf schools across the continent (November 16-17), then converging on Orange County for its own meeting (November 18-20) and finally a regional conference (November 20-21).

Dateline Freeport ME: Line-Up of Clusters for Foundation Studies

Nine clusters of foundation studies stretching from coast to coast have started up or resumed this year. Here is a brief listing of clusters new and ongoing.

Nine clusters of foundation studies stretching from coast to coast have started up or resumed this year. Here is a brief listing of clusters new and ongoing.

Foundation Studies Year One programs are underway in the following centers:

- Anchorage, Alaska

- Chapel Hill, North Carolina

- Denver, Colorado

- Gainesville, Florida

- Phoenix, Arizona

Foundation Studies programs continuing with a Year Two program include:

- Waldorf School of Atlanta, in Decatur GA

- Cincinnati Waldorf School, in Cincinnati OH

- Merriconeag Waldorf School, in Freeport ME

- Lake Champlain Waldorf School, in Shelburne VT

For details outlining the next round of foundation studies, check this page or contact Barbara Richardson, Coordinator of Foundation Studies, at:brichardson@centerforanthroposophy.org

Dateline Wilton NH: Listing of Renewal Courses 2015

The following courses will be offered in CfA’s annual Renewal Courses this coming summer

Week I (Sunday 21 June – Friday 26 June 2015)

The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily: Performing the Story with Marionettes

With Joan Almon, Janene Ping, Debra Spitulnik

The Paths of Intuition: Educating with Insight, Courage, and Joy

With Christof Wiechert

Laying the Foundation: Teaching Grade 1

With Christopher Sblendorio

Finding the Middle Path: An Exploration of the Landscape of Grade 2

With Kate Golden

Working with the Image of Man at the Heart of Waldorf Education: Teaching Grade 4

With Dennis Demanett

The Golden Age: Grade 5 in a Waldorf School

With Patrice Maynard

The Turning Point of Childhood: Teaching Grade 6

With Helena Niiva

How to Survive 8th Grade and Come Out Smiling!

With Darcy Drayton

The Gift of Drawing: Blocks and Blackboard Preparation for the Classroom, Grades 1-8 With Elizabeth Auer

Music in the Morning: Singing and Recorder Playing in the Classroom

With David Gable

Foreign Languages in Grades 1,2, and 3: Kindling Imagination, Cultivating

Understanding, and Practical Language Skills

With Kati Manning and Lorey Johnson

The Four Temperaments

With Adrian Locher

The Brave New World of Seventh Grade

With Sue Demanett and Louis Bullard

Week II (Sunday 28 June – Friday 3 July 2015

Healing Aspects to Address Trauma in Childhood, Adolescence, and in Biography

With Michaela Gloeckler

Anthroposophy and Buddhism: The Reality and Possibilities of Relationship

With Michael D’Aleo

Re-Imagining Mathematics

With Jamie York

Nature’s Alphabet: Exploring the Relationship between Word and World

With Paul Matthews and Patrice Pinette

Roots, Leaves, Flowers, Seeds, and Spirit: The Ancient Art of Healing with Herbs

With Deb Soule

Michelangelo for Beginners: Carving in Marble

With Daniel O’Connors

The Art of Christianity: A Journey through Art History

With David Lowe

Embracing the Darkness

With Charles Andrade

Social and Organizational Issues

With John Cunningham, Barbara Richardson, and Torin Finser

Self-Education through Intuitive Thinking and Artistic Perception

With Signe Motter, Hugh Renwick, Elizabeth Auer, and Douglas Gerwin

Co-Workers, Sisters, and Friends: Women Students and Spiritual Researchers around Rudolf Steiner With Christopher Bamford

Dateline Wilton NH: Stepping into High (School) Gear

For the 20th year in a row, the CfA’s Waldorf High School Teacher Education Program (WHiSTEP) will launch a new summer session for prospective and practicing high school teachers. Douglas Gerwin, founder of this program, briefly previews the forthcoming cycle.

The next round of our three-summers program starts in July 2015 on the campus of High Mowing School, a Waldorf school in Wilton, New Hampshire. As in previous years, we will be offering specialization in:

- Arts/Art History — with Patrick Stolfo

- Biology and Earth Science — with Michael Holdrege

- English & Foreign Languages — with David Sloan

- History and Social Science — with Meg Gorman

- Mathematics and Computer Studies — with Jamie York

- Physics and Chemistry — with Michael D’Aleo

The schedule is arranged in such a way that students can specialize in either one or two of these areas.

The program, begun in 1996, also features hands-on seminars in “Living Thinking” with Michael D’Aleo, “Human Development and Waldorf High School Curriculum” with Douglas Gerwin, and “Professional Research” with Michael Holdrege, as well as workshops in drama (David Sloan), eurythmy (Laura Radefeld), music (Jeff Spade), sculpture (Patrick Stolfo), and speech (Daniel Stokes).

In addition to these three summer intensives, students undertake two years of independent studies including a research project and internship. At present over 110 current students and graduates of this program are working in around 50 Waldorf schools across North America.

Details of our forthcoming summer program–starting on Sunday 28 June and running until Saturday 25 July–can be viewed here on our website.